Indoor strawberry growers have faced high disease burden, crop loss, and ultimately revenue loss—challenging outcomes for an emerging industry trying to establish a foothold in Canada’s food production system. The VertBerry team of Université Laval is reimagining how the provision of disease-free transplants to Canada’s growers can propel and strengthen the industry.

The team will use a vertical farming system based on aerobioponics to fully control the environment; this means growing plants without substrate while integrating beneficial microbes. The approach eliminates pests and produces young plants with consistent, reliable qualities and yields.

Led by Dr. Martine Dorais, the team works across every aspect of production to ensure the success of their approach, testing and developing new berry cultivars adapted for indoor systems, customizing the engineering behind modular vertical farming technology, and validating the quality of transplants before they reach growers. By carefully matching cultivars to specific growing environments and extensively testing plants, the team aims to build a new level of trust for their diverse customers—outdoor, greenhouse, and vertical growers alike. Growers can rely on the pedigree, expertise, and judgement of all partners in the supply chain, ensuring consistency and confidence in every transplant.

A cornerstone of the project is the health of the transplants and hygiene management of growing systems, led by François Gagné-Bourque of Ulysse Biotech. “Our technology is based on green chemistry and the use of microbes,” he explains. “Traditional cleaning methods don’t work for living systems like greenhouses. By actively managing the microbiome, we can prevent pests and diseases from forming and taking hold, tailoring them to each crop, and provide growers with the tools to maintain healthy, productive plants all season long.”

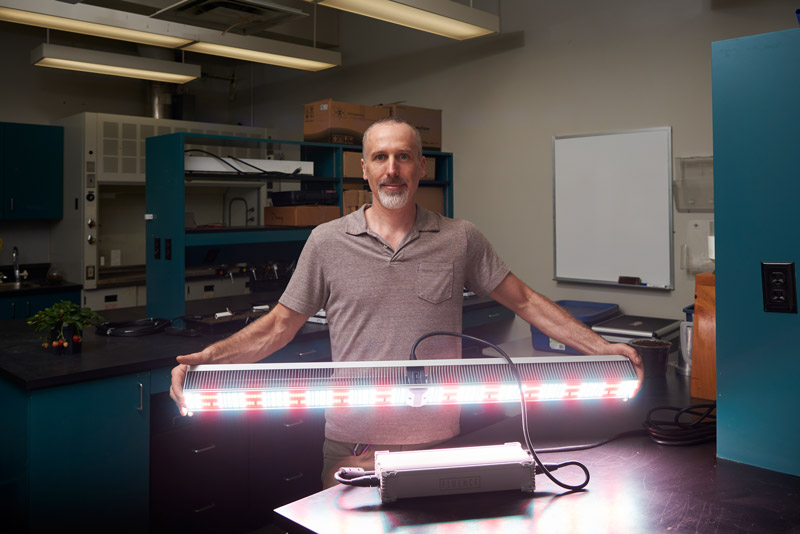

Romain Schmitt, founder of Farm3, helps customize vertical farming units for growing transplants and testing new cultivars. “Everything is designed around what the plant needs to thrive,” he says. At Farm3, vertical farming serves as a precision research tool—not to replace traditional growers, but to empower them and help them achieve sustainable profitability by boosting yields and reducing uncertainty.

Vincent Hall is the project’s partnership and integration lead and CEO of Pépinières Cultivar Inc, the partner responsible for the technology and supplying healthy, acclimated transplants to commercial producers. He describes the approach: “Success isn’t just about technology or biology, it’s about having the right people in the right roles and making sure everyone’s expertise is connected. We’re creating an ecosystem where knowledge, experience, and practical insight all come together.”

L to R front: Claire Letanneur, Martine Dorais, Vincent Hall, Thi Thuy An Nguyen

“Our work isn’t just about producing plants, it’s about creating a system that can adapt, innovate, and support growers over the long term,” Hall says. “If we can make these cultivars thrive indoors, we can open the door to a new way of growing food responsibly and intelligently.”

The team works closely with growers, commercial partners, and researchers to ensure their innovations translate to real-world impact. “By integrating agronomy, engineering, and microbiology, we can build systems that are reliable, scalable, and tailored to the needs of industry,” Dorais adds. Education and professionalization are central to the project. From hygiene and microbiome protocols to acclimatization of transplants, the team equips growers with knowledge and tools to stabilize their yields, increase resilience, and focus on continuous improvement rather than daily firefighting. This professionalization will also attract a new generation of growers, drawn by predictability, profitability, and opportunity.

By addressing a major challenge faced by indoor strawberry growers, Université Laval’s VertBerry project is working to strengthen the Canadian greenhouse sector, increase profitability, and build a resilient, sustainable food system.

Collaborators

- Cultivar

- Ulysse Biotech

- Farm3

- Demers

- Gush

- A. Massé Nursery

- Savoura

- Modulable

- Lightbase

- Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food of Quebec / Ministère de l’Agriculture, des Pêcheries et de l’Alimentation (MAPAQ)