This project truly revolves around the sun. A solar energy expert at Western University is applying open-source photovoltaic technology to optimize the use of the sun’s energy to support both indoor and outdoor production of different varieties of berries. Modular and scalable, the production system can be adapted to growing conditions across Canada, including the north, and could ultimately produce enough energy to supply far more than farms.

Agrotunnel agrivoltaics hybrid for sustainable food production.

Western University researchers are devising an extraordinary twofer of technological advancements that could unlock an incredible amount of untapped potential on Canadian farms. Working with private partners, the team is coupling an indoor vertical farm with a shielded outdoor farm to create a low-carbon growing system that will extend the growing season of multiple types of berries. This dual-environment approach could one day even generate power for non-agricultural use and be attached to retail locations to provide a zero-mile food supply.

The key to increasing productivity in both indoor and outdoor growing spaces is agrivoltaics—specialized solar panels that both allow the transmission of natural light to plants underneath while also producing electrical energy—to turn solar energy into electricity on agricultural land. “It could be massively beneficial,” says Joshua Pearce, the John M. Thompson Chair in Information Technology and Innovation at Western University, where he holds appointments at both the Ivey Business School and department of electrical and computer engineering.

“A small percentage of Canada’s farmland turned agrivoltaic could take on all of our electrical needs.”

Five types of berries will grow outdoors under adjustable photovoltaic (solar) arrays, where plants will be protected from extreme weather and require less water than conventionally produced crops. Energy collected by the arrays will power the lights, water pumps, and heat pumps of the indoor vertical farm, decreasing energy demands and costs.

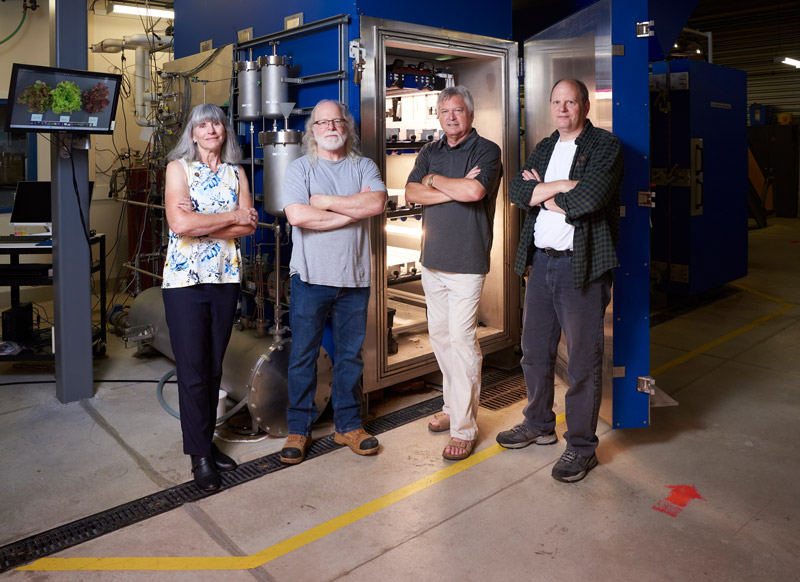

The vertical farm will be housed within an agrotunnel supplied by Food Security Structures Canada, a Métis-led controlled-environment growing company. The agrotunnel is a fully sealed chamber made of a lightweight fibre-reinforced polymer that can be above ground or buried to evoke J.R.R. Tolkien’s imaginary hobbit houses when covered with earth and vegetation. Inside, blueberries and strawberries will be planted on grow walls, while raspberries, blackberries, and ground cherries are grown in bins along horizontal rows. “The density is crazy,” Dr. Pearce says. “It’s like walking into a library where every row of books is strawberries.”

The vertical aeroponic hybrid system uses peat cups and a coco-coir medium (which are pest resistant without the use of chemicals) and high-efficiency, spectrally optimized LED lights. Plant health will be monitored by open-source computer vision, machine learning, and artificial intelligence systems designed in the Free Appropriate Sustainability Technology (FAST) lab in collaboration with electrical engineer Soodeh Nikan. Raymond Thomas, Western Research Chair in the department of biology and the scientific director of the Biotron Experimental Climate Change Centre, will investigate the nutritional profile of the berries to determine how the growing methods influence food quality.

Modular and scalable, the production system can be adapted to growing conditions across Canada, including the north, and could ultimately produce enough energy to supply far more than farms. “It’s giant,” Dr. Pearce says, recalling his early research into agrivoltaics’ potential in North America. “It was like, ‘Guys, this is it. This is what we should be doing.’”

Collaborators

- Shawna Ferguson, Western University

- Janice Kelsey, SolarCities

- Kim Parker, Food Security Structures Canada

- Tabatha Siu, Vertical Green

- Jody Spangler, Adragone Aeroponics

- Greg Whiteside, Food Security Structures Canada